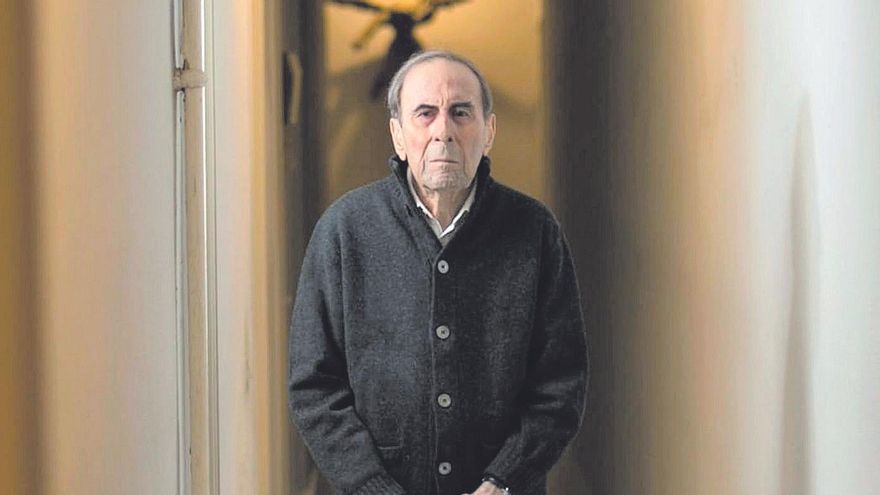

«Look, my brother, do you know? We have never departed from Altamira; “We remain in that Cave: we share the same need to evoke as many fears as those nameless artists felt whilst they frightened away the bison,” states Cristino de Vera (Santa Cruz de Tenerife, 1931), who, from an early age, has worked to rekindle in each canvas the very candles one blows out on their birthdays. To achieve this, he employs the embers from pages marked with crosses in the almanac, for in him, as in very few others, existence and art are entirely intertwined. Those candles for his 93rd birthday, celebrated on December 15, are elongated indeed; just as he recently received the Great Distinction of Nivaria from the Cabildo of Tenerife in its inaugural edition, his exhibition, Cristino de Vera, the painter of silence, was concluding at the Cervantes Institute in Paris.

«But who are we? Creators, artists, or something else? We are merely beings, nothing more, the product of the chemistry and physics of our parents. It requires just a little time spent in the desert, or on a deserted beach, or beside a tranquil river, to comprehend the insignificance of the ego. Had I not pursued painting, I would have aspired to be a metaphysical philosopher or an astronomer, to validate this belief. I hold the conviction that we all possess a spiritual essence, though many stray due to greed and envy; the paramount lesson is to learn to eliminate vanity, that dreadful plague causing chaos in present-day art,” cautions De Vera, leading by example: «I have always understood that I am simply a steward of my own existence, and thus, I have endeavoured to paint as distantly as possible from my own self.»

Thus, aware with Dante that, if Hell exists, it is egos that burn there, Cristino distances himself from this double bind: not only is there no trace of egotism in his canvases; there is not even a singular instance—something far rarer—in the hand that creates them. With his renowned unbelieving humility, he acknowledges that he feels equally fulfilled with having not only fulfilled his vocation but doing so devoid of any ostentation. It is one of his most gracious qualities (in both a religious and secular context, as per one’s preference): giving the impression that there is no individual behind his paintings. Absolutely no one (but perhaps, everyone), under the aura of its unmistakable mysticism of light mysteriously drizzled, at once metaphysical and tangible, expressionist and intimate, warm and hieratic, plastic and within the chassis, chrome and radiographic, eternally assessing the precise juncture between life and death; or rather, the inner life of death.

Truly a pure man, it is charming that the painter of silence is so articulate. He speaks in rhizomes, like the roots of various Canarian endemics, as he pauses for breath, punctuating his statements with a knowing warmth: “You perceive me, don’t you, brother?” A heartfelt refrain, which he appears to utter, with Franciscan symmetry, not just to any bipedal conversational partner, but to all that surrounds him, which he approaches with an alert curiosity and a matured tranquillity, simultaneously akin to a senile child.

The artist, who at a tender age of 20, discovered a welcoming monastery, perfectly suited to his needs, in a loft beside the Madrid Rastro, recalls that, long before, nothing was as pivotal in his development as observing the light and silence at La Tejita beach, with its totemic Red Mountain, in Granadilla, where his mother was born. That open and serene geometry, resembling a vault exposed to the elements of his adolescent summers, was the origin of his eventual devotion to desert landscapes. Particularly contrasting to his numerous visits to the Luxor desert in Egypt. Yet, beyond that evocative connection between the pintadera and the pyramid, De Vera advises: “No one should forgo a visit to some type of desert; everything and nothing exists there, a mirror reflecting who we are and who we will become.”

And, as he has remarked, for him, “God, or however one may refer to them, is the silence radiated from natural spaces: that light which is only heard when we relinquish our ego.” In truth, “infinity resides within us, and that is why I constantly seek for the light to emanate from the painting itself,” he articulates.

He claims to share with Einstein a “relative faith in Spinoza’s pantheism,” and he learned from Kant the “necessity for universal good,” as well as that “deep slumber is the twin sibling of death.” In fact, he discusses his preferred thinkers and artists as though he observes them parading, in levitation, down the corridor of his Madrid home in Chamberí. Or wherever, as one of his chief attributes is his ability to utilise critics lauding his status as an “extemporaneous” artist to feel contemporary across all eras. “I have always found inspiration walking beneath the starry sky of Segovia, endeavours to witness it as Saint John of the Cross and María Zambrano perceived it,” explains De Vera, while also paying homage to Tagore, Gandhi, or Buddha, from whom “I have sought to learn to dispel suffering.”

Similar to his paintings, the painter attains transcendent insights from the peak of immanence and lightness, while now they accompany him, as he names them, akin to his brothers: Juan Sebastián Bach with his cherished Aire suite; El Greco and his vibrant verticality; and Fray Angelico, imparting that essential guidance of “silver blues and greys”…

Their clear and amiable skulls (which could equally serve as gánigos for sipping wine, or as guests to share it) are always found on the precise boundary separating the hereafter from the hereafter, drawing a clear origin from the famed litany of TS Eliot: “In my beginning is my end.” For his creations, the distinction between cradle and graveyard awaiting him, himself, and one after another, all his fellow humans, disappears. “It appears astonishing that they do not realise it,” he seems to murmur quietly, as with that imaginary almond which the elderly seem to chew in their mouths.

To those who have known him for an extensive period, it is not difficult to perceive that Cristino de Vera (so inextricable from his paintings, we reiterate, for he does not exist behind them) has evolved in synchrony, both vertically and horizontally, like the crosses and the crossbones on the skulls, the wrinkles in the shrouds, the radiance, and the shadows, in shared solitudes, invoking the final landscape as if it were the original one, in order to – precisely – exorcise it.

«The aim of art, due to its dreadful and contradictory approach to beauty, is to learn to die,” he says. “If this was evident to me from a young age, imagine now,” he continues, cherishing the fact that over the years, he has had much more time to partake in one of his cherished pastimes: donning headphones to enjoy music in silence, to truly listen to the silence. “Take my counsel: if you ever encounter a problem, irrespective of how substantial it may be, put on some headphones disconnected from any device, find a quiet spot, and listen to the silence; you will soon see how it fades away… You understand me, right, brother?

Subscribe to continue reading