Sor Milagros or Secrets of Cuba, the sixteenth installment of the Atlantic Library, prologued with documentary authority by Manuel de Paz Sánchez and published in 2022, with spelling correction of the original text, is a Canarian historical novel by Aurelio Pérez Zamora (Puerto de la Cruz, 1828-Santa Cruz de Tenerife, 1918), an author whom Joaquín Artiles and Ignacio Quintana, in their History of Canarian Literature (Excma. Comunidad de Cabildos de Las Palmas, 1978) place next to Francisco María Pinto de la Rosa and Rafael Mesa y López as the most distinguished representatives of the insular narrative of the 19th century.

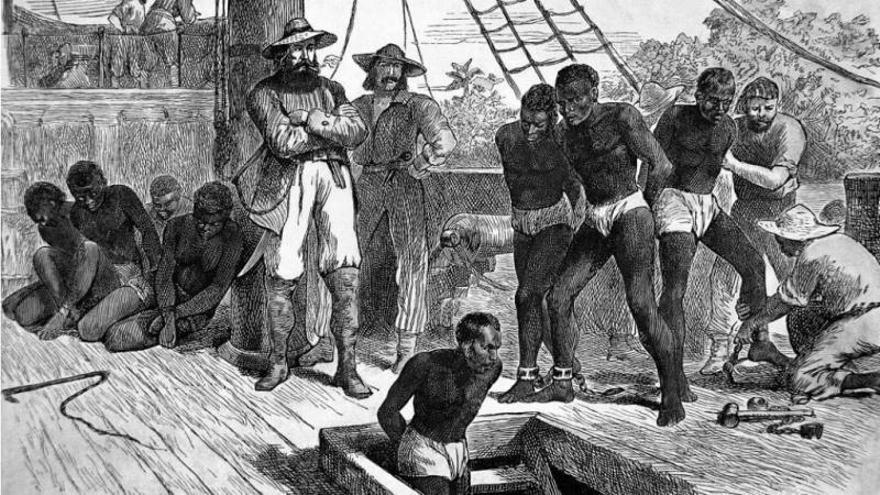

Sor Milagros… is a novel in which, through forty-seven chapters, or what Pérez Zamora calls “several pictures” linked together, events that occurred in Cuba in the mid-nineteenth century are recounted, pictures of pain and cruelty in a colonially corrupt Antillean country, with slavery and the island’s desire for independence as a backdrop.

A version of nineteenth-century Cuba given by an islander that in no way coincides with the views that, from mainland Spain, were directed at one of their last overseas possessions and what really happened there.

A novel in which more or less true characters coexist with others invented by the writer. Among these fictional characters, the most outstanding: Ángel García, Cabeza de Perro, the pirate who never existed, remotely inspired by the figure of the corsair from Tenerife Amaro Rodríguez Felipe, Amaro Pargo, whose activity took place between the 17th and 18th centuries.

Over several years, and in different places (Madrid, Santa Cruz de Tenerife), the author, Aurelio Pérez Zamora, accidentally meets a man whom he tries to identify without success, until he finally sees him again in Paris. and there they both finally recognize each other: this man is Antonio Gonzalga, a fighter for the abolition of slavery and for the independence of Cuba, and he had met Pérez Zamora in Havana, where the Puerto Rican writer had lived for a good part of the 1850s.

In Paris, they become friends and the author asks this extraordinary man to tell him everything that has happened to him throughout his stormy life in Cuba. The different stories that Gonzalga tells the author in Boulogne Park, New York’s Central Park in Paris, for several days become the axis of this novel: his relationship and impossible love with Sister Milagros, a nun from the institution Daughters of Charity, who at the end of the book turns out to be her sister by blood, the corruption politics and social crisis of colonial Cuba in the mid-nineteenth century, the slavery abuses, the independence struggles, which will cost Gonzalga two death sentences from which he escapes at the last moment, the impunity for committing crimes by some obscure and unscrupulous characters (the pirate Ángel García, Cabeza de Perro and his son, Luis García; His Excellency Don Fermín de las Cañadas, an accomplice of Ángel and Luis García, and the miser Don Prudencio) owners of all the sordid businesses in Havana that they manage from an ancient building full of architectural defects located in the Calzada de San Lázaro neighborhood of the Cuban capital.

As we have already said, Ángel García, Cabeza de Perro, is a myth built on the exploits of the corsair Amaro Pargo. And as we already know from Paul Valéry, “myth is the name of everything that does not exist and is only present thanks to the word”. And apparently, the first words that raise the figure of Cabeza de Perro are due to Aurelio Pérez Zamora and his historical novel Sor Milagros o Secretos de Cuba, published for the first time in Santa Cruz de Tenerife in 1897. But as such a myth, as symbolic fable, myths never stop supplying themselves with infinite situations with certain analogies, and they grow and develop or complement each other, and this is the case of Cabeza de Perro, which has even gained real legality from its true existence through feathers as authorized such as that of the Cervantes Prize, the Cuban Dulce María Loynaz, that of Professor Pablo Quintana Déniz, author of an edition of Sor Milagros… (Editorial Benchomo, La Laguna-Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1986) or that of the official chronicler himself from Santa Cruz de Tenerife, José Manuel Ledesma, three authors who, without entrusting themselves to God or the devil, have come to correct the alleged biography of the character created by Pérez Zamora to offer us additional profiles on life of the famous pirate who never existed, although popular fantasy has catapulted him beyond the simple words that gave birth to him through Aurelio Pérez Zamora.

Both in the case of Loynaz and that of Quintana Déniz or Ledesma, the resounding candor is surprising when they refer to aspects of the life of Cabeza de Perro such as the existence of his house in Igueste de San Andrés, in Tenerife, or when They tell us that in that dwelling, to which the ferocious pirate returned from time to time, was part of the booty of his Atlantic and Caribbean raids.

In Sor Milagros… novels by Eugenio Sue and Alejandro Dumas are cited, novels read by Luis García, the son of Cabeza de Perro, and which serve to give his crapulous life an exculpatory literary dimension. It is not unreasonable to affirm that it is those romantic fiction historical novels that inspire Pérez Zamora when constructing his work, full of stormy and surprising loves and of even more unexpected origins and filial kinships (as we have already mentioned, Gonzalga is the brother stolen in her earliest childhood by a servant from Sister Milagros’s mother, Sister Micaela, Superior of the Daughters of Charity, where Sister Milagros enters to profess, she is her sister for a “crime” of adultery by their common mother ), and to also add to that romantic register a naturalistic halo from the hand of Émile Zola, in regard to his attempt to describe the crudest, sordid and macabre part of reality, as we can see in one of the chapters of Pérez Zamora’s book, such as the one entitled El taller del Crimen, or in the third and fourth chapters, where the protagonist pirate appears exhibiting his cruelty in its maximum version.

The construction of Sor Milagros… in forty-seven chapters, or “frames”, often with jumps in the action and plot alterations, is constantly justified by the author of the work through the frequent apologies that his interlocutor-narrator offers him. throughout the story, as we can see on page 192, where don Antonio Gonzalga says to Pérez Zamora: «Forgive me for the saint gone to heaven by separating me from the main thing of the relationship. Where were we?”. Or on page 509, where Gonzalga himself apologizes again: “But let’s leave this and now let’s move on to something else even if I digress in my story.”

However, the main plots and secondary plots of the novel are perfectly linked and at the end of its reading we have quite clear profiles of its most prominent protagonists and secondary characters, which is surprising in an almost first-time author in the narrative genre. .

Undoubtedly, the loves of Gonzalga and Milagros are superimposed on what the description of the raids of Cabeza de Perro will mean, a character who, however, serves Pérez Zamora to x-ray us the rotten colonial Cuba in contrast to the idealisms of Gonzalga in his capacity as a committed citizen as well as almost sickly in love.

Aurelio Pérez Zamora published Florence or characters from other times in 1902 in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, with thirty-nine chapters and with Carlota la Cubana’s daughter as the protagonist. Carlota, a very important character of Sor Milagros…, was the daughter of the owner and merchant Pancho Marti kidnapped by the henchmen of the most excellent Mr. Fermín de las Cañadas, the accomplice of Ángel and Luis García, and the miser Prudencio. Florence, the protagonist of this second novel by Pérez Zamora, is told to us in the last pages of Sor Milagros… and this information is complemented by Sebastián Padrón Acosta in his 19th-Century Canarian Altarpiece (Aula de Cultura de Tenerife, 1968), where we describes this second installment of Pérez Zamora, as a novel of «scenes, customs and vices» of the Spanish society of the 19th century», in which literary characters such as Arcastel, anagram of Castelar, and Tonibe, anagram of Galdós appear. According to Padrón Acosta, Pérez Zamora’s narrative prose is under the influence of the aforementioned Galdós and Father Coloma, an opinion that we do not participate in due to its partiality and reductive nature.