This is the description of Santa Cruz by the Irish travel writer Olivia Mary Stone:

“When on September 5, 1883, the Paraná dropped anchor in the anchorage of Santa Cruz, health inspectors approached the side of the ship in an elegant boat to carry out the procedures that would allow us to disembark, the towers of the two main churches stood out clearly above the houses; however, the beauty of the landscape lay in the wide and extensive curve of the bay, enhanced by the sea foam breaking on the beach and the tranquil waters of the anchorage, on whose surface boats of various shapes and nationalities floated. Everything formed a peaceful and pleasant scene of a gleaming city, with the Anaga mountains in the background rising before the abrupt end of the bay, giving it a majesty rarely matched, with its uneven and serrated profiles raising its wild ridges in a sky blue in a way that is grand, beautiful, and awe-inspiring. The valleys hidden in these lonely spots, watered by mountain dew and warmed by a subtropical sun, must be lonely corners to enjoy and explore.”

As we disembarked after dinner, we had to pay double to the boat that took us to the dock for the journey and the luggage transport. When we jumped into the boat, we had to pay full attention to do so when it was at the crest of the wave. The man at the helm was incredibly attractive, dark and handsome; however, the four skinny and gaunt sailors rowed as if they were overcome by excess energy, so in a few minutes we reached the dock.”

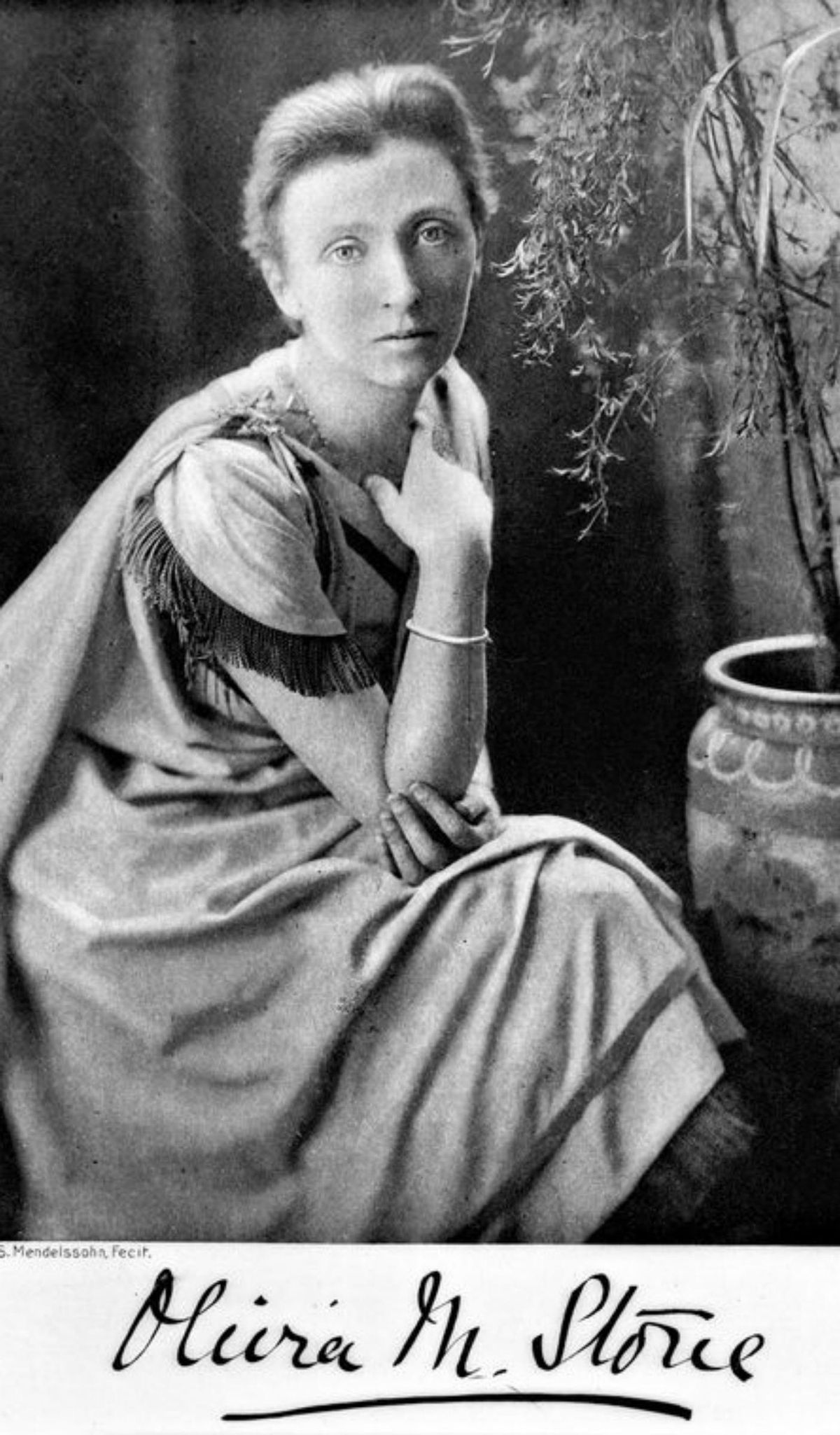

Olivia Stone | | ED / José Manuel Ledesma Alonso

Overwhelmed by a heat we were not accustomed to, we walked to Hotel Camacho (Calle San Francisco, 11), where we were relieved to be able to sleep without feeling everything was swaying. Our beds were surrounded by mosquito nets and we only covered ourselves with the sheet, although we didn’t even need it to keep warm. As we enjoyed our first sleep, both this and the tranquility were interrupted by a loud, somewhat musical shout from the street by the night watchman: ‘It’s one o’clock, all is well!’

In the morning, it took us an immense amount of time to get dressed, due to the sounds and sights happening in the street that compelled us to approach the window, either to see a man driving a pair of oxen with a rope tied to their horns to guide them, while prodding them with a stick to hasten their pace, or elegant ladies dressed in black, with attractive mantillas and fans, on their way to Mass, the daily and almost sole exercise of Spanish women. The rest of the women wore a coat tied over their heads and falling down their backs, thus protecting the nape from the sun and sporting a small round straw hat on their heads.

Men usually wear black trousers and white shirts, with a handkerchief or any piece of cloth cinching the waist. The hats are felt, round, black, and wide-brimmed. Children go barefoot and only wear a short, loose shirt.

After breakfast, we strolled along the dock right in front of the hotel, which is the main attraction of Santa Cruz. The dock juts out into the sea at a right angle to the beach, forming a sort of pier that, although not usable by the boats, is very practical for disembarking in rowboats. At the beginning, there is a small fish market, with marble counters and tiled walls and floors.

A locomotive, carrying stones to complete the dock, traveled down the middle of the street, where three camels remained kneeling awaiting their heavy load. Each of them had bells hanging from their necks to warn pedestrians of their presence, as the silent steps of their padded hooves were not audible.

When we arrived at Constitution Square at 10:30, the thermometer read 80°F (26.6°C). This open space, surrounded by tall and stately houses, has at the bottom a monument, erected by the Spaniards to commemorate their victory over the Guanches, formed by a column of Carrara marble, crowned by a Virgin and the Child. At the base, there are four life-size figures of the treacherous Guanche kings looking upwards. Below the kings are four cherubs.

Continuing our journey, we reached the church of La Concepción, located near the ravine. More English people attend this church than any other in the Canary Islands, as it houses the flags recovered after Nelson’s attack. The island of Tenerife and the city of Santa Cruz pride themselves on the honour of defeating him in 1797, causing him to lose an arm. The flags, what hurts us the most and they love the most, were not taken but found. Nelson himself, in a letter to General Gutiérrez, who commanded the troops from Tenerife, acknowledges the bravery of the inhabitants and the courtesy shown afterwards; incidentally, the first letter signed with his left hand.

The church holds another item of interest, a small wooden chapel entirely carved, which is found upon entering a door.At the right of the altar (Chapel of San Matías – Family Carta Pantheon).

Leaving the church, we crossed a bridge (El Cabo) supported by huge columns over a completely dry channel. The last time water ran through this ravine, it swept away the bridge.

On the other side of the ravine is the hospital, a fairly large building where new sections are being added, and the old part is being renovated. Besides being a hospital, the building also serves as an orphanage, nursing home, and asylum. The Sisters of Charity take care of the sick and abandoned children.

In the afternoon, we walked to the northern area of the city, visiting along the way the church of San Francisco, which is located on a small rise in the city center. The church is attached to a huge building housing a museum and a school for children.

Leaving the church, we continued our walk along a long and narrow street parallel to the sea (Calle de La Marina), which, like the rest of the city’s streets, is paved with cobbles. The outer walls of the houses are whitewashed, and some have large wooden crosses hanging, some even up to six feet tall (two meters). The roofs of the houses are tiled, although some have rooftops where they have set up lookouts for merchants to spot the arrival of ships and be the first to reach the dock to acquire the goods they transport.

One of the most characteristic features of the houses is the window shutters; each one has external shutters and two foldable wooden pieces in the lower half, used as hatches with upper hinges. As one walks along what appears to be a silent and deserted street, these hatches or shutters gradually open outward, one after another, revealing attractive faces full of curiosity, with dark skin and hair. In the poorer houses, where the doors are always open, the whole family gathers in the doorway to watch us pass by.

Continuing along this street, we arrived at the fortress of San Miguel (now the Yacht Club), from where we had a good view of the bay and the northern coastline. At our feet was a beach of grey volcanic pebbles (San Antonio beach) with long fishing nets spread out over it.

That night, the Philharmonic Society of Santa Cruz was giving a concert in the Alameda near the hotel. The musicians with string instruments performed remarkably well some Strauss waltzes and the Canarian Songs by Teobaldo Power, a local composer. Although these gardens are public and belong to the City Council, the entrance fee is three Euros, which includes a number for a raffle. The well-lit walks with oil lamps hanging on both sides had benches under the trees. At the end of the main avenue was a covered kiosk, filled with labelled and numbered items, where you handed in the small rolled piece of paper you were given at the entrance. Placing it in a plate of water would unfurl it, revealing the name of the prize you had won, such as a mirror, a bottle of beer, a vase, porcelain ornaments, etc. Although the paper was almost always blank.

The atmosphere in the park was enchanting. The strollers were young men and women, mostly from the middle class. They wore suits of white, blue, or vivid pink and sported flashy and modern hats, although the ladies dressed in black wore elegant mantillas. The night was warm, and our thermometer read 80º F (26.6º C), as if it had gotten stuck.

I have been told that concerts held before the onset of the hot season are attended by a higher social class audience because the wealthier citizens have moved to their country houses in La Laguna and other areas.

(*) Olivia Mary Stone (Ireland, 1856-1898) arrived at the port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife accompanied by her husband, the London photographer John Harris Stone, with whom she travelled through the Canary Islands for six months, stopping in each town to converse with the locals and capture photographs.

Her book, Tenerife and its six satellites, provides the best portrayal of island society in the late 19th century, describing the Island as the center of attraction in the Archipelago, as from Teide, the other Islands are seen as genuine satellites revolving around it. This work would be a perfect propaganda guide for Tenerife, not only due to the narration but also the abundance of drawings and photographs it contains. Upon her departure, in response to the praise she received from the Tenerife press, she replied, “We will always remember them as they seemed to us, truly happy islands, the closest thing to an earthly paradise.”.