Cinema is undergoing its own changes as a form of artistic expression, and the literature that influences it, whether from historical research, criticism, or in-depth language study, is taking on new and intriguing directions aimed at a development increasingly adapted to the pace set by the new paradigms in audiovisual culture. This means that we must stay constantly vigilant of the rapid changes happening around us, especially since new technologies have emerged as valuable tools for exploring the complex sociocultural scenario portrayed by the iconosphere of the 21st century at all levels.

At the same time, 68-year-old Jorge Gorostiza (Santa Cruz de Tenerife) in his book “Architecture + Cinema + City: Constructions and Perspectives” (Asymmetric Editions, 2023) asserts that moving images have transformed our perception of the urban and architectural landscape. In today’s panorama, it is more important than ever to know how to observe, to construct a vision that detects symptoms of what is happening even in seemingly banal aspects that are ultimately crucial.

The evidence of this assertion is prominently highlighted in this fascinating collection of articles compiled by the seasoned Tenerife writer in his latest publication, with a singular and enlightening purpose: to present a new approach to the phenomenon of moving images in light of a perspective that combines the canonical interpretation of audiovisual language with the viewpoint provided by an architectural reading of that language.

Gorostiza, one of the leading Spanish authorities in his field, emphasizes this idea, extensively discussed in a bibliography that now exceeds fifteen volumes, according to which cinema is as indebted to architecture as modern architecture is to cinema. This implies the existence of mutual correlations from which both media have drawn over their history, consolidating a long and fruitful association through a dense catalog of films belonging to diverse genres and trends.

Among the numerous research projects regarding the connections between major cities and cinema, he discovered, in 1930, the existence of an old feature film project titled “Barcelona,” starring Janet Gaynor, John Garrick, Kenneth MacKenna, and Humphrey Bogart, to be directed by none other than John Ford. Naturally, this never went beyond being a mere news item in the Exhibitor Herald World and was never brought up again.

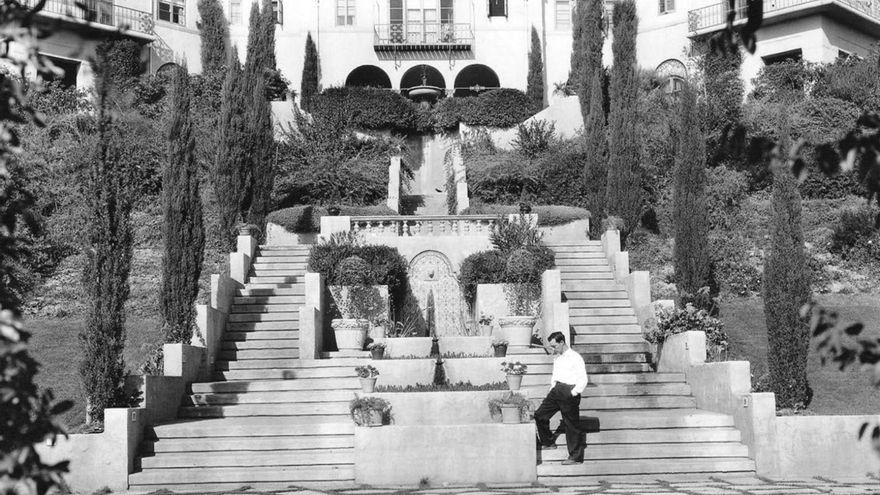

It is for this reason that Gorostiza includes articles in his new book, previously published on his blog, explaining this hybridization from the era of silent cinema to the present day, measuring the extent of the influences described in the dozens of pieces that make up this engaging and innovative “declaration of principles.” He also reveals historical data, events, and anecdotes that shed light on lesser-known aspects for the cinephile community, such as the use of Buster Keaton’s old and sumptuous mansion in Beverly Hills for the filming of “Parlor, Bedroom and Bath” in 1930, or the appearance of Virginia Travis, one of the first female characters practicing architecture on screen, portrayed by Miriam Hopkins in the comedy “Woman Chases Man” (1938), directed by the American filmmaker John G. Blitstone and, at least in our country, unreleased. Gorostiza highlights the character’s proto-feminist profile, considering that this production was made 86 years ago.

In a specific moment of the film, the architect tries to convince a millionaire of the merits of her project using words that would have surely angered any censor: “I know what you’re thinking, that I’m a girl, that’s for sure,” “I have the courage of a man, for seven years I have studied like a man, I have researched like a man, and there is nothing feminine in my mind. Seven years ago, I gave up a serious commitment to an older gentleman, because I chose to have a practical career. I left him at the church door to become an architect, and today I am prepared and he, on the other hand, is dead,” asserts Miriam Hopkins.