The current architecture, the one that is being built today, is not truly sustainable, rather it is soft, it does not reflect that each place is a different place that requires to be different, and because it is not sustainable to install a solar panel on top of the roof. By the way, poorly designed plates, little iron, planned obsolescence and future garbage that we will not know what to do with.

He Canary archipelago It is a land where this false sustainability is underway even if it is harmful: minimal walls, paper windows, glass facing the afternoon sun, holes not oriented to get more shade, structures like those from 60 years ago.

Is what is made with natural materials sustainable? Do we import them? Wooden houses? And where does that wood come from? Doesn’t wood burn? Doesn’t it require repairs every year? And poisons against moths? Would they resist a Delta or a flood? Thank goodness we have volcanic stones.

No, not all natural materials are used to build a safe Canary Islands, resistant to the attacks of nature, that is, designed in understanding with nature, designed for that adaptation that the climate (track by track) is asking us to have. consider.

You cannot build the same in all countries and places. It is normal to use bamboo in Hong Kong but not in Tenerife. Likewise, it is normal to build in Tenerife with volcanic stone but it is not normal in Singapore.

In defense of concrete

Recently, in Singapore, at the World Architecture Festival, I kept hearing bad things about concrete as a highly polluting construction material. It squeaked at me. It is one of the big mistakes that architects as a group are making. I began to review the history and, of course, I returned to Rome with the eyes of an apprentice. To convey the power and prestige of their empire, the Romans built lasting architecture as a symbol of their long-lasting reign. Emperors used large public works as an affirmation of their status and reputation. That architecture, made with Roman concrete, has survived to this day, and that concrete only contaminated once 2,000 years ago.

By contrast, Japanese architecture has long embraced ideas of change and renewal, evident in the ritual reconstruction of Shinto shrines. For me this is much less sustainable than preserving the concrete of the Pantheon in Rome and not demolishing everything that can be preserved, following the teachings of the Pritzker Lacaton and Vasal prizes.

Durability as a goal

Let’s imagine a tropical cyclone larger than the Delta that we suffered in 2005. Where would we prefer to be when the hurricane winds arrive, in a Sinoist sanctuary or sheltered by the walls of the Pantheon in Rome? Of course I choose Rome. And just as in Rome and Japan, around the world, philosophies around permanence and demolition, destruction, permeated and permeate architectural traditions but now we are in a global world and in the midst of a climate crisis that is here to stay. .

The paradox of sustainability

The paradox of current sustainable architecture is that we will know nothing about its durability and adaptability to the climate that human beings will need in 20, 30 or 40 years.

Contemporaries continue to create structures as symbols of power, preeminence and pride. Olympic stadiums, for example, represent a country’s ability to host global events and leave behind iconic monuments. These structures often become obsolete once events conclude, raising concerns about their long-term viability and sustainability. For example, the Bird’s Nest Stadium in Beijing, despite its initial grandeur, struggles to attract consistent use and generate revenue, as if revenue is now the biggest problem.

In the ‘non-negotiable’ phase

Yes, sustainable design becomes non-negotiable: as severe weather and climate change attack the built environment, sustainable design goes from an option to an obligation. The point is that, from the projects seen, there is a lack of environmentally conscious design with the necessary capacity to mitigate risk.

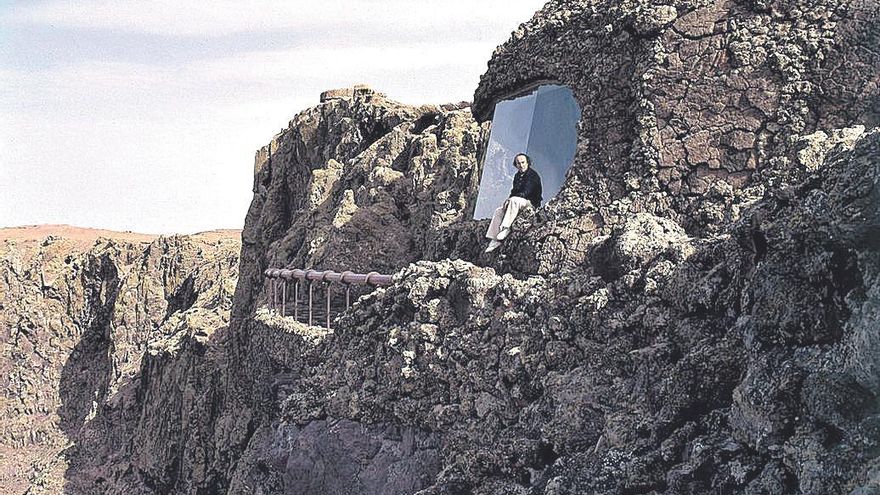

Sustainable today is a building that has been in use for 40, or at least 25 years and that has required nothing more than minimal maintenance. We have an example of concrete and volcanic stone that I love at home: the Mirador del Río de Cesar Manrique in Lanzarote. Another is the College of Architects of Tenerife, by Vicente Saavedra and Díaz Llanos. That is sustainability. Both examples feature concrete and have proven their durability, adaptability and timeless beauty.

dulce Xerach Pérez

Lawyer, doctor in architecture, researcher at the European university