The Spanish Protectorate of Morocco, also called ‘Spanish Morocco’, was part of the Sultanate of Morocco as a consequence of several Spanish-French treaties that culminated in 1912 with the distribution of the territory, with Spain corresponding to the northern area, with the regions of Yebala, Gomara and the Rif, where the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla were located. France was given the rest of the sultanate, coincidentally its richest regions. Soon, the inhabitants of the Rif took up arms against the Spanish troops originating a bloody campaign known as the Moroccan War, which produced serious human losses and damage to the Spanish army deployed in that area.

A wave of solidarity arose throughout Spain, promoting surveys, collections, donations and subscriptions to help the victims and the Army. One of these proposals was formulated on August 3, 1921, in the newspaper La Verdad de Murcia, by a captain of the Civil Guard, José Martínez Vivas. In his letter he pointed out the possibility of each Spanish province offering the Army an airplane.

The campaign called Los Aeroplanos del Pueblo was a great success and resulted in the acquisition and donation to the Army of a total of 39 airplanes, from 17 provinces (four of them from the Canary Islands), foreign territories such as Cuba or Manila, newspapers such as La Avant-garde and individuals such as the Belgian citizen George Marquet or the former senator Eusebio Giraldo.

In the newspaper LA PROVINCIA of August 13, 1921, the first reference to this topic in the Canary Islands appeared in the headline, an article titled For the Homeland, which ended with these words: “And how those feelings must crystallize into facts, and we We see in the public sentiment the desire to be promoted to greater companies, without prejudice to the establishment of a board that will bring our proposal to successful success, we begin today, as has been done in other provinces, a public subscription to acquire a airplane for the Army that with the name ‘Gran Canaria’ is an expression of our tribute and adherence to the Homeland. THE PROVINCE subscribes 250 pesetas for that object.

The four French Breguet XIV airplanes donated by the Canary Islands were the Island of La Palma, the Canary Archipelago, Tenerife and Gran Canaria. On January 15, 1922, at the Tablada airfield (Seville), along with 16 other aircraft, the Island of La Palma was handed over to the Army, blessed by Archbishop Eustaquio Ilundain and sponsored by Her Majesty Queen Victoria, represented by Infanta Doña Luisa. In turn, the Canary Islands and Tenerife were handed over to the Army on July 3, 1922, at the same airfield, also blessed and sponsored by the same people. They all had aluminum shields representing each island on the sides of the fuselage.

The delivery of Gran Canaria to the Army, together with the Madrid aircraft, took place at the airfield of the capital of the State Cuatro Vientos, on Saturday, June 24, 1922. Later, on August 1, LA PROVINCIA published an extraordinary issue narrating at length the events that occurred in said event.

The first list of donors was published in this newspaper on August 20, 1921, amounting to a total of 560 pesetas and was headed, after the newspaper’s contribution, by citizens of the city of Telde.

As a result, income amounted to 43,157.90 pesetas, and expenses were 39,433.05, which left a remainder available of 3,724.85 pesetas.

The expenses are broken down into the 38,779.40 pesetas that the device sent to Madrid cost, the 400 pesetas for the aluminum shields and the 250 pesetas that were given to the family of the gunner Eduardo Cabrera as a donation.

The Breguet In total, about 8,000 units were built. In Spain, with a total of 140, some of them nationally built, they entered service in 1919 and remained in flight until 1934.

This newspaper, on June 25, 1922, published a heartfelt article in which it stated that “THE PROVINCE was able to carry out such a patriotic undertaking, using the offers that, in large numbers, reached its editorial office,” adding that “it entrusted the Delegate of His Majesty’s Government the unlimited mission of establishing a Board. The article continued saying that “this was done, with us even renouncing to be part of it; Although, later, and corresponding to a feeling of delicacy on the part of our esteemed colleague, the Director of the Diario de Las Palmas, who was appointed to represent the press in the aforementioned Board, and who resigned his position because he understood that it was we who should occupy it, our Director was a member of the executive committee of the pre-appointed Board.

“THE PROVINCE wants nothing for itself and is very satisfied with having provided Gran Canaria with this new expression of its patriotism,” it stated in its edition. At this point in the story, I believe that no one would doubt that the island of Gran Canaria owes its plane to the initiative and efforts led by the newspaper LA PROVINCIA.

In 1923, it was considered appropriate by the Chief of Military Aeronautics, General Soriano, to take advantage of a period of relative calm in the Moroccan war to organize an air expedition to the provinces furthest from the homeland, in this case the Canary Islands. , as a demonstration of the desire to protect their most distant territories and, at the same time, as gratitude for the donation of the airplanes to the Spanish army.

three of the four

A year later, in January 1924, the Canary Islands, Gran Canaria and Tenerife carried out the raid from Larache (Morocco) to the Canary Islands, piloted by Captains Pardo García and Martínez-Esteve, and Lieutenant Pisón, accompanied by observers Captain Bermúdez. de Castro, Lieutenant Rexach and mechanic Bosch. A Dornier Wal seaplane from the El Atalayón base (Melilla) acted as escort. The Isla de La Palma did not participate, probably because it was damaged or destroyed.

Official organizations, city councils, neighborhoods, civil societies, military units, educational centers, companies, parishes, ships and individuals participated in the survey. Popular events such as festivals, evening parties, soccer matches and theater performances were also promoted. The Island Council collected 2,464 pesetas and the City Council of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 2,469.

The seaplane, crewed by captains Franco and Mas de Gaminde, with mechanics Mateo and Panizo, and camera operator Leopoldo Alonso, left Melilla on the 3rd heading to Cádiz, where it picked up commander Delgado Brackembury, head of the expedition. . The next day the Dornier left for Larache, where the Breguets were waiting for it, but due to unfavorable weather circumstances throughout its journey it was impossible to accompany them, making its flight alone to Cape Juby, where it arrived on the 17th, after passing through Ceuta. Casablanca and Mogador, the attention received in the latter place being so great, where it was on the verge of shipwreck, that they baptized the Dornier with the name of the civil governor’s daughter, Marie Antoinette. The Breguets had arrived at Villa Bens (Cape Juby) on the 14th and, at the request of the head of the post, Colonel Bens, they made some flights through the interior of the Sahara, to the great expectation of the natives.

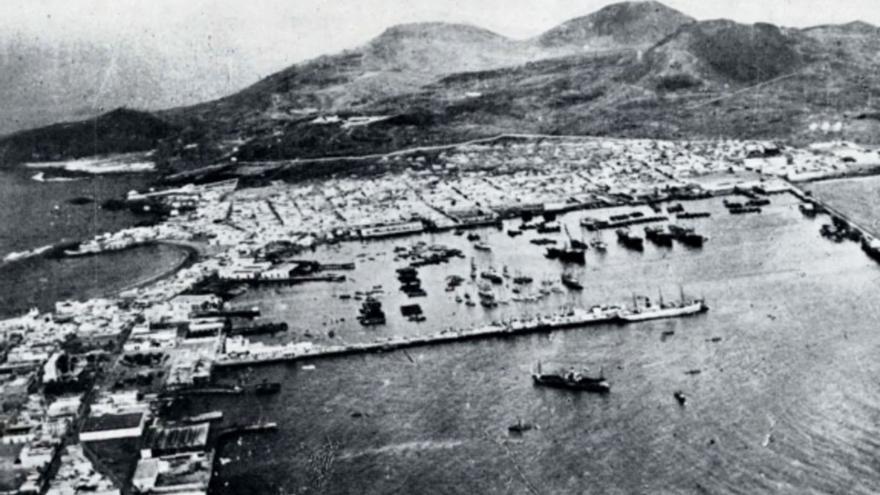

On January 18, the four planes took off from Cabo Juby and headed to Gran Canaria, landing safely in the Páramo de Gando los Breguet, while the Dornier, in which Colonel Bens was traveling as a guest, did the same in the Port of Light. Kindly, all the crew decided that the so-called Gran Canaria would be the first plane in history to land in Gando, with Lieutenant Juan Martínez de Pisón, who had the immense honor of piloting it, accompanied by mechanical corporal Juan Bosch Guitart.

A crowd of people awaited the arrival of the aviators in the Gando moor and escorted them to the city with a caravan of more than 200 cars, with all the crew staying at the Metropol Hotel.

Indescribable, according to cameraman Alonso, the raid’s reporter, were the entertainment, dances and banquets offered by the city’s civil entities such as the Mercantile Circle, Literary Cabinet, Nautical Club or the City Council. The 22nd was the culmination, with the presentation by distinguished ladies of Canarian society, to each member of the expedition, of gold and silver medals alluding to the aerial journey, in an emotional garden-party that took place in the gardens of the Hotel Saint Catherine.

Previously, on the 21st, courtesy flights called baptisms of the air were carried out for certain people, including the accidental mayor of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Juan Ortiz, or Pepe Gonçalvez, founder of the Real Club Victoria. The Tenerife, which landed after the Gran Canaria, its pilot blinded by the dust devils, rammed its tail, destroying it and permanently disabling the airplane.

On the 30th the raid ended with a flight to Tenerife for the two remaining Breguets and the Dornier. Upon landing on a poor improvised airfield in Arico, the Tenerife capped and was also disabled. The head of the expedition, Commander Delgado, made the decision to end the raid for the land airplanes, dismantle them and return to their origin by sea. Needless to say, in Santa Cruz de Tenerife the countless entertainments and demonstrations of enthusiasm for the presence of the aeronauts were repeated.

The newspaper La Gaceta de Tenerife of the 31st reported the heartfelt words of the first deputy mayor of the capital, Mr. Ravina, at a lunch held at the Town Hall, referring to the fact “that the Tenerife and Gran Canaria airplanes had suffered damage, and that nevertheless the Canary Archipelago will continue intact, dictated by providence, which, because it is fair and because it is the aspiration of the Region, will maintain the unity of the archipelago intact, without there being sufficient reasons to violate it.

The seaplane, before embarking on the trip, flew over Teide, where cameraman Alonso took the first aerial photographs of the volcano, barely due to the extreme cold that he experienced in the open cabin of the plane’s nose. He left, definitively, on February 7. He would make the flight back to his base, after a technical stopover in Lanzarote to refuel and other Moroccan locations.

The sentiment of the Canarian people towards the entire Spanish nation was perfectly demonstrated in those difficult times of hardship and needs of all kinds. Our famous and immortal countryman, Benito Pérez Galdós, despite shaking off his shoes when leaving Las Palmas for Madrid in 1867, used to say, referring to the Canarians, that “the closer we are to the Homeland with the heart, the further away we are by the distance”.